Theatre Interview with Shanta Gokhale: There is a great need for documentation

- Deepak Sinha

- Mar 9, 2018

- 8 min read

Shanta Gokhale is a writer, translator, cultural critic, and theatre historian. Generations have learned from her reporting on theatre and culture which include young theatre enthusiasts, theatre directors, actors, writers, and journalists. Her discussions and writings on theatre are a source of clear and precise knowledge of play-making in Mumbai, un-muddled by tradition or ramblings of the memory. Shanta tai won the Maharashtra State Award [the best novel of the year] for her novel Rita Welinkar in 1992. Again, she won the Maharashtra State Award for Tya Varshi [the best novel of the year] in 2009. She has witnessed playmaking with Soli Batliwala, Ebrahim Alkazi, Vinod Doshi, Satyadev Dubey, Dr. Kumudini Arvind Mehta, Arun Kakade, Sulabha Deshpande and Sitaram Kumbhar. She has also written the screenplay for the Hindi film, Haathi ka Anda (2002). She acted in the parallel cinema classic film, Ardh Satya (1983) and a 13-part TV series directed by Amol Palekar. She has also translated plays by Mahesh Elkunchwar and Satish Alekar. In the year 2016 she was awarded The Sangeet Natak Academi Award for her overall contribution to the arts. India Today calls her the "Grand Dame of Marathi theatre" in an article. She writes a column for Pune Mirror and Mumbai Mirror [since 2006].

This Women's Day Rasa Aur Drama is delighted to bring an interview with her where she chats her book published by Speaking Tiger.

Rasa Aur Drama: Could you tell Rasa Aur Drama the need for a book: An Oral History of Experimental Theatre in Mumbai ?

Shanta Gokhale: There is a great need for documentation. I have always been very keen on it. Criticism gives you a single viewpoint. Documentation brings in multiple viewpoints. This helps future generations to see an issue from all sides and make up their own mind about what is valuable for them and what is not. This is the reason why, when I edited my earlier books on the work of Satyadev Dubey and Veenapani Chawla, I held my critical voice back and allowed other voices to enter through newspaper articles, reviews, and interviews. I had sorely missed the documentation of plays and processes when I was writing my book on Marathi theatre, Playwright at the Centre. All I found were books filled with anecdotes. There was neither a rigorous critical viewpoint nor a fix on dates and hard facts.

Shanta Gokhale

"The book could have been conceived in several ways. But we thought of making it an oral history because once again it was a way of bringing in many voices."

Nearly 20 years ago I had asked Chetan Datar who was working very hard to revitalize the old theatre group Awishkar, why he didn't start documenting its activities from the time of its inception, through the Chhabildas movement to the present when the entire climate of theatre-making and reception had changed. He agreed this should be done. But when it came down to the practicalities of doing it, someone who was busy making theatre could not be expected to have time for documenting it. With this in mind, I had proposed in a small talk I gave in Pune that each theatre group which was doing serious work should persuade a non-performing member to join, only to be an observer and record the processes involved in the making of the group's plays. At that time I had cited my discussion with Chetan about documenting the Chhabildas movement as an example of what could have been done but wasn't. Some people in the audience took up this idea. Ashok Kulkarni one of the founder-members of the Sahitya Rangabhoomi Pratishthan Trust and the driving spirit behind both its fellowship programme and the Vinod Doshi Theatre Festival, took up the idea and shared it with Sunil Shanbag. Together they decided that Chhabildas did indeed need to be documented but also the other movements that led up to it. That is how the idea for The Scenes We Made was born. The book could have been conceived in several ways. But we thought of making it an oral history because once again it was a way of bringing in many voices. The book would then be a valuable collection of several memories about the same time, place, people and activities, but some which matched each other and some that clashed with each other. A documentation through the lived experience of some of the theater's most prominent actors, directors and technicians had, according to us, a value beyond a book that was authored by one person.

Q2.) Could the book have clarified the reader’s understanding of Experimental theatre through the oral telling of the playwrights and actors?

SG: As the editor, I wanted to stage a discussion of the idea of experimental theatre itself. The title claimed that the book was an oral history of experimental theatre. But what was experimental? In the times with which the book was dealing, the term experimental had been animatedly contested. That is why one of the questions we briefed interviewers to ask, was how interviewees defined experimental in terms of the theatre they had done. Did they think they were doing experimental theatre? Most of the interviewees said they had not been consciously thinking in those terms. Not surprisingly, the three interviewees, G. P. Deshpande, Pushpa Bhave and Rajeev Naik who did offer a critical analysis of the theatre of the times seen in the context of what they thought experimental meant or should mean, were academics. The book does not state this or that is experimental. It says here is a contested idea and this is how the serious thinkers in theatre look at it. To my mind, leaving it open gets the reader closer to the truth of the concept than closing the argument with a definition that would at once simplify and falsify the issue.

Shanta Gokhale

"I think the Marathi, Bengali and Hindi theatre people would find it interesting if translated. There was talk of its being translated into Marathi. I don't know if it is happening."

Q3.) The teaching method and persona of Satyadev Dubeyji are so intriguing and driving; as recorded in the book by Sunil Shanbag, Amol Palekar, Gerson da Cunha, Girish Karnad and others. Could you tell us about your interaction with Dubeyji ?

SG: My interaction with him extended over 50 years. It was a friendship in which he and I discussed many aspects of theatre, in which he directed Avinash the first play I wrote, in which I became part of his theatre circle where I found lifelong friends. It was a great learning experience for me to watch his rehearsals. The friendship also involved a falling out occasioned by his losing his temper with me because my daughter [Renuka Sahane] gave up theatre to become a television actor. The quarrel from his side lasted for over a decade and then we were friends again till the day he died. When I edited a book on him, I wanted to give him a copy. He barely looked at it saying it didn't interest him. He never spoke of the past nor did he live in it. But when Ashok Kulkarni interviewed him for the oral history, he couldn't stop talking about the past. Ashok recorded four videotapes of his disconnected but gushing memories. Perhaps he saw his end coming and finally felt it was time to talk.

Q4.) Playwright Badal Sarcar’s works were being translated in Hindi, Vijay Tendulkarji’s works in English, Girish Karnadji’s in Marathi, Mahesh Elkunchwar’s plays into Kannada. Would this book also see translations in many languages ?

SG: I think the Marathi, Bengali, and Hindi theatre people would find it interesting if translated. There was talk of its being translated into Marathi. I don't know if it is happening.

Shanta Gokhale and Veenapani Chawla

"Dubey directed a very strange play called Aesopcha Goggle which made no sense to anybody. We wondered whether it had made sense to the playwright himself!

Q5.) The book has accounts of theatre at Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute, Walchand terrace, and Chhabildas School Hall. Could you recount your experience of any of them?

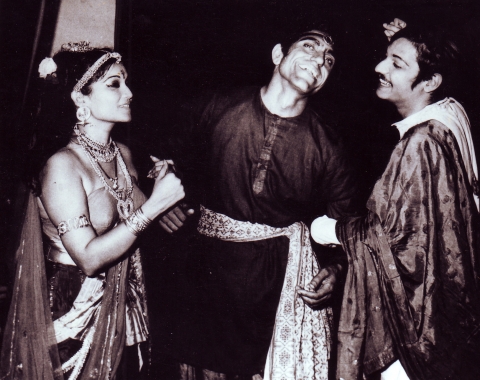

SG: I was out of the country during the heydays of the Bhulabhai Desai Institute. I used to visit Walchand Terrace once in a while. It was always buzzing with activity. But being a rehearsal and adda space, one met interesting people there but didn't see plays. I saw the greatest number of plays at Chhabildas. They introduced me to some of the most important and innovative playwrights and directors of the time. I have vivid memories of seeing the Marathi adaptation of Lorca's Yerma directed by Jayadev Hattangady with Rohini Hattangadi playing the lead role. Jayadev used the central space of the hall for his production. The other Jayadev-Rohini play that has stayed in my mind was Medea with its magnificent tiered set and a brilliant performance by Rohini. Jayadev and Rohini were both from NSD [National School Of Drama] and brought the aesthetics of that school to Chhabildas. Plays directed by Dubey were much more ascetic. The two productions of his that caused a stir because of the totally different perspective they brought to Marathi theatre were Shyam Manohar's Hriday and Yakrut. Dr. Shreeram Lagoo's production of G. P. Deshpande's Uddhwasta Dharmashala was memorable both because of its form, its political purpose, and Dr. Lagoo's performance. In later years there was Bhumiticha Farce written and directed by Shafaat Khan, a hilarious take on how human beings think in terms of categories; and there were several productions by the newly formed Antarnatya group. I remember seeing their Marathi adaptation of Tom Stoppard's The Real Inspector Hound and Rajeev Naik's translation of Midsummer Night's Dream as Ain Vasantat Ardhya Ratri. These are only a few of the many plays I saw between the mid-seventies and the late eighties. There was of course much more to Chhabildas than seeing plays. As important as that was staying back to discuss what we had seen. The interest in theatre was so high and passionate that discussions could go on for hours and spill into the following few days. Some of the plays were superb and some downright bad. But we watched them all because it was important to see what writers and directors did with word, space, and movement when given freedom to follow their imagination. The definition of the word experiment is trying out something new with no guarantee of results. Dubey directed a very strange play called Aesopcha Goggle which made no sense to anybody. We wondered whether it had made sense to the playwright himself!

Q6.) Do you think the book can still be taken forward, into something like a history of experimental theatre across the country?

SG: Yes absolutely. But not as one book. I think the histories of all important theatres in the country need to be separately recorded. Each deserves a book by itself. Extremely interesting experiments have taken place in Bengali, Kannada and Malayalam theatre. Books on each of them would make valuable additions to Indian theatre scholarship.

Q 7.) What challenges did you face in putting together a book on theatre?

SG: The challenge was specific to the form that we had chosen for this book. However rigorously we had briefed the interviewers and however sharply they stuck to the focal points given to them, interviewees were apt to ramble. That is what memory is. You can't hold it back once it gets going. My challenge was to select and order the material to fit the focus of our study. To make the book readable, it had to be so structured as to create a narrative that was easy to follow. In order to do that I had to read through pages and pages of transcripts to pick out just those portions that fitted the focus and scope of our book. Since the rest of the material was also valuable, Sunil worked on it with Sucharita Apte and it has all been uploaded on Sahapaedia.

The image gallery runs you through some voices in the book:

About the Writer:

Deepak Sinha writes on theatre at My Theatre Cafe and now at Rasa Aur Drama. He loves to cycle and play basketball. He loves to organize TEDx conferences and is an organizer at TEDxPune. He also curates theatre content for his online newspaper The Drama Daily.

Comments